I was wildly in love and wanted it to go on forever. I was gambling on infinite possibility… but my timing was off.

On Missoula Avenue, we lived in a house that had a small gas heater in the living room, and no heat in the two, small bedrooms. To keep warm, we had to leave the bedroom doors open. In the six months of cold weather, whenever the wind blew, the single-pane windows all whistled. Cold leaked into the house like the constant dripping of seawater that plague submarines in old WWII movies.

The bathroom in that house was so small that there was not quite enough room for the toilet and the bathtub; I had to sit slant-wise to find room for my feet, and sit upright in the 3 foot tub –like a cowboy in a Saturday night wash basin.

We moved into that house when my boy was 2 months old. It had a big, overgrown backyard with an apple and a plum tree. When he was just starting to walk, we built a chicken coop out of hay bales and hatched 5 hens from eggs under a heat lamp. The chickens would let my boy walk up to them and touch them, but would never let the two of us get close; they would 'baaaw 'and 'qwaaa' and flap away.

My boy had been born premature and had spent his first few weeks in an intensive care unit, but the first year at the Missoula Avenue house had felt so good and we still wanted more kids. We were always broke, we were paying off my boy's huge medical bills, and I didn't make much money because I worked as a software consultant. This was long enough ago that very few people had computers, and the only places I could find to pay me for software were doctors and the large local hospital, St. Pats. Then, to make more money I stopped being a consultant when St. Pats offered me full time work.

But even with a bit more money, the house became too small. And the winter was long and windy. Even though my boss was a good man, the hospital administration was not, and I was not used to the sort of kowtowing that went with being employed by a catholic hospital. Instead of writing code, most of my time was spent configuring computers and fixing broken printers and teaching people how to do mundane tasks. The hospital's main administrator had looked at my resume and ignored my history of inventing technology, ignored that I had been employed as a think-tank software engineer, and instead keyed in on my one year as an elementary school teacher. He told my boss, "He's an educator." I put on a tie and spent 40 hours a week teaching people how to use Lotus 1-2-3 and Word Perfect.

We all have our pockets of memory that we touch, that becomes our moods. I have good memories that I keep dear; Many tiny moments in that Missoula Avenue house with two small kids that help me when things are dark. Children learning to talk and their words coming out of laughter over surprises: soft toys wrapped in bright paper, sweet food discovered for the first time on the end of colored plastic spoons, bath times in the 3 foot bathtub with warm water splashing from awkward hands trying to — delightfully trying to — grab hold of bubbles.

I hated my job. I started to hate my wife. I hated the small space of that house, the drafts, the spiders that would crawl in through the cracks, the lack of space.

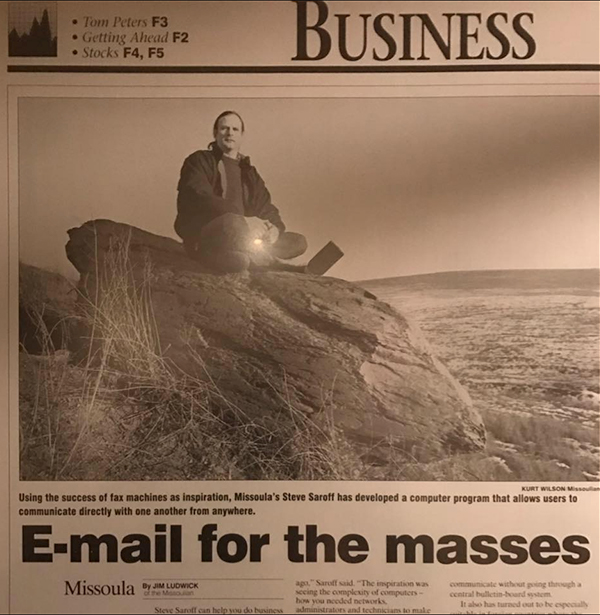

I had an idea. I thought that computers would become communication devices. I convinced a friend of mine to work on this idea with me. He worked by day at Microsoft in Seattle. He worked at night on our idea. I worked at night on our idea. Kids would go to sleep, and I would go to a computer and a stack of technical books. I had to teach myself new programming languages. I had to learn network protocols and modem technology, and graphic interface design. I would work until exhaustion. I wasn't able to talk, to communicate. I know my wife hated me too.

A skunk dug under the door to the chicken coop and killed all the birds. My boy raced out of the coop one morning terrified; he had found them, all of their heads ripped off. The hot water tank line kept freezing in a sub-zero winter, and angrily I couldn't afford a plumber and had to spend time fixing things. Our car broke down. Other things broke. The clothes dryer. We hung the kid's clothing around the space heater. I have a photo from that time's Christmas. The kids were surrounded by a sea of torn wrapping paper and simple presents that made them very happy. Behind them were hanging cloth diapers and clutter of clothes hampers and blankets and my wife's unsmiling face. I know that I was just as bitter.

I overheard a conversation. I had quit my job at st. pats to work full time on FreeMail. No money was coming in. She was saying on the phone, "He thinks everyone will have computers in their home. I don't know what to do." She was right to worry. I was gambling on a future, and no future is predictable.

Being right doesn't help the past. We had started to get some money for my idea. Not much, but enough to get me traveling to places where I would evangelize what email could do for large corporations. It was worse than teaching accountants how to use spreadsheets. I had convinced the Kinko's chain that my software would change the way they did business, and they had started using FreeMail but had their lawyers find ways to keep from paying me much. I had to fly to Los Angeles every two weeks, rent a car, and drive the two hours up to Ventura. Most people at the company didn't want to change how they were doing things, and I would only get paid if all of the Kinko's stores started using FreeMail. In 1995 very few people understood what was coming. Typewriters were still being manufactured. I had been right about what would happen, but I was wrong about how long it would take.

Near the end of things, she picked me up at the airport one night with the two kids. This was when everyone was still allowed to go up to the gates. When my flight landed and was taxing on the runway, I looked out at the airport, and there, glowing in the dark of a winter night, were my two kids standing against the terminal windows, waving at the plane, waving at where they knew I was. All of the exhaustion of LA freeways and meetings in windowless conference rooms faded; I was home. Then I got off the flight, and she and I didn't connect, and when I got in the car, the floor by my feet was cluttered with garbage: junk mail, food wrappers from McDonald's happy meals, and other trash. The first questions she had were about money. I had no good answers.

I was begging investors to get involved with my ideas. I was desperate for a way to any kind of financial stability. When a subsidiary of WorldCom, WamNet, offered to buy FreeMail and give me a steady paycheck, I took the offer. Then WorldCom went bankrupt, WamNet went into a tailspin. It took three months before I was fired. In those three months, she left, and we were officially divorced, ironically, on the same day I was in a meeting where I got myself fired for cussing at the WorldCom CEO. I had asked, in front of a room of WorldCom and Enron and WamNet officers, "What part of 'Fucking idiot' don't you understand?" I had directed this at a famous person who should have been in jail for what he was doing with investors' money, and in fact, was sent to jail about a year later. But being right isn't any good without good timing. When I asked him my question, he stared at me, and then got up and left the boardroom. A few minutes later, the building's security guard as well as the company's Chief Legal officer, walked in and told me I was to be escorted out of the building. Two hours before I had gotten a cell phone call from my wife, who told me that the marriage was over.

I was now raising two kids without steady money. I spent the next three years buying broken radios on eBay for $25, fixing them, and reselling them for $50. I also built people websites for $150. But mostly, I went to the job service and got day jobs hanging sheetrock or loading construction trash into dump trucks. There was no market for software engineers. The Dot Com Crash happened at the same time as my crash. People who say that money doesn't matter have never been broke.

I've got all this space now. Two paid-off houses. One of them is on 20 acres of mountain forest. Big bathrooms, even though I like most just walking outside in the woods and peeing, especially at night when the sky is clear, and there are thousands of stars, and I still see infinite possibilities. I still love the feeling of unpredictable, beautiful space where I can go in any direction. I like having rooms filled with books and notebooks. I like that I can work on my ideas now without having to be fearful of losing a place to live, without being fearful of not being able to take care of the people who matter to me. But success is still as elusive as ever. Which is a great thing. You see, I still have a long way to go.

#

Additional Steve S. Saroff writing

- Success - a short story

- FreeMail - some of what happened

- Back story of Paper Targets

- The First Chapter of Paper Targets

- The Amazon page for Paper Targets

- The Long Line Of Elk - Poems and Artifacts

- My dyslexia

- Letter To My Daughter - a love story in Redbook (A bit about how it was published here)

- Wildhorse Island - another Redbook story

- 1972 - Leaving Home

- Jewel Boots - a short story set in Missoula

Contact Steve S. Saroff

- Website: Saroff.com

- Podcast: Montana Voice Podcast

- Instagram @SteveSaroff

- Facebook steve.saroff

- LinkedIn SteveSaroff

- Threads: @stevesaroff

- GoodReads: Steve S. Saroff

Flooding Island

Montana Voice, a Podcast, is a Flooding Island Production. All content on the MontanaVoice.com website and on the Montana Voice podcast are copyrighted. Copyright © 2000 through 2023 by Flooding Island LLC. and by the individual copyright holders. Montana Voice™, and MontanaVoice.com have been online since February 2000. The Montana Voice Podcast is also distributed through Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and wherever you listen to podcasts.

Montana Voice™, and Flooding Island™, and the Flooding Island logo are trademarks of Flooding Island,LLC.

Contact us through social media or by email: info AT floodingIsland DOT com